Visiting Scholars

Once Marstrander and Flower had discovered the Island it was almost inevitable that others would follow once word of the place had spread. And so it transpired.

Over the following years, a steady trickle of scholars with a special interest in Irish language and culture made their way to the Great Blasket. Among them were the Swede Carl von Sydow, the French linguist Marie Sjoestedt, and such distinguished Irish scholars as Myles Dillon and Daniel Binchy.

The publication of An tOileánach in 1929 and Fiche Blian ag Fás four years later introduced the Great Blasket to an even wider audience. During the summer months of the thirties, a steady stream of language enthusiasts, teachers and civil servants visited the Island. They hoped to practice their Irish or to meet the famous Islandman in person. Hence the numerous photographs of Ó Criomhthain posing patiently with the book in hand. Cultural tourism had arrived on the Great Blasket.

John Millington Synge (1871-1909)

John Millington Synge visited the Great Blasket in the late summer of 1905. He came not to learn Irish, but as a travelling writer seeking inspiration for his work.

And indeed his travels along Ireland’s western seaboard, and especially his among the island-dwellers of the Blasket and Aran Islands, provided the inspiration for some of his finest work as a dramatist. His play The Playboy of the Western World is regarded as a classic of modern theatre. The rich language and strong personalities of the leading characters are probably modelled on island people Synge would have encountered.

Though many of the islanders took offence at what Synge wrote about them in his posthumously published In Wicklow, West Kerry etc, his observations are nevertheless acute, and noteworthy for their unsentimental mixture of sensitivity and detachment.

The whole site of wild islands and sea was as clear and cold and brilliant as what one sees in a dream, and alive with the singularly severe glory that is in the character of this place.

Carl Marstrander (1883-1965)

Carl Marstrander was the first of the many able scholars of linguistics to visit the Great Blasket. He arrived in the autumn of 1907 to learn modern Irish. With Tomás Ó Criomhthain as his teacher, he was soon able to converse at reasonable ease with the islanders. Besides being a scholar, Marstrander was a man of considerable athletic ability, being an accomplished pole vaulter. Such physical prowess probably endeared him further to the islanders who gave him the affectionate nickname of “An Lochlannach” (the Scandanavian).

After a few months he left the island and returned to Oslo. He kept in touch with Tomás by letter for a while. On one occasion he asked Tomás to send him a list of the island’s flora and fauna in Irish. Marstrander was the first visitor to arouse in the islanders, and particularly in Tomás Ó Criomhthain, a sense of the value and uniqueness of their language and culture.

Robin Flower (1881-1946)

Having read classics at Oxford, Robin Flower joined the manuscripts department of the British Museum in 1906. In 1910 he came to study Old Irish under Carl Marstrander at the recently founded School of Irish Learning in Dublin.

Encouraged by Marstrander, he came to the Great Blasket to learn modern Irish in the summer of 1910. His teacher was Tomás Ó Criomhthain. The following summer he returned with his wife on honeymoon. As his competence in the language grew, he began to record some of Tomás’s stories. These were posthumously published as Seanchas ón Oileán Tiar (Stories From the Western Island) in 1956.

He visited the island many times in the twenties and thirties, bringing his young family with him. The islanders gave him the affectionate nickname ‘Bláithín’ (Little Flower). He distilled his love affair with the island and its people into a short but intensely felt book, The Western Island, in which he evoked the grandeur of the island’s landscape and the character of its people.

When he died in 1946 his ashes were scattered about An Dún, the highest point on the Island.

Brian Ó Ceallaigh. (1889-1936)

Brian Ó Ceallaigh was born at Killarney and educated at Clongowes Wood and Trinity College Dublin. Soon after qualifying with a law degree in 1913 he developed an interest in learning Irish.

He arrived on the island in April 1917 and spent the rest of the year learning Irish from Tomás Ó Criomhthain. Ó Ceallaigh was to play a crucial role in developing the creative writing talents of his teacher. It was he who first encouraged Tomás to record his life and the daily life of the island in his own words. He gave him Pierre Loti’s “Iceland Fisherman” and a selection of Maxim Gorky’s stories to read. These books inspired confidence: if the lives of Icelandic fishermen and Russian country people could provide the basis for such literature, why not the life of a Blasket islander or the lifestyle of his community? When he left the island on New Year’s eve, he made a gesture that showed his respect for Tomás as a writer: he gave him his Waterman fountain pen.

In poor health and unhappy with his job as a schools’ inspector, Ó Ceallaigh left Ireland in 1923. He took the manuscript of Tomas’s journal with him, but failed to find a publisher. He eventually entrusted it to Padraig Ó Siochfhradha, who edited and published Allagar na hInise (1928) and The Islandman (1929). Ó Ceallaigh died in Split, Yugoslavia in December 1936.

Tomás is a writer, a fisherman, a farmer with one cow and a stonemason too. He handles words as he handles stones: he makes pictures with them.

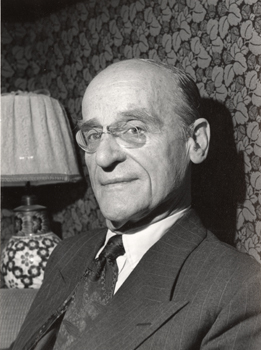

George Thomson (1903-1987)

George Thomson, a young Cambridge classics scholar, came to the Great Blasket to learn Irish on the advice of Robin Flower in August 1923.

He very soon formed a close and enduring friendship with Muiris Ó Súilleabháin, a young islandman of his own age. When Muiris left for Dublin to join the Irish Police (Gardaí) in 1927, it was George Thomson who met him off the train. The publication of Ó Criomhthain’s The Islandman in 1929 provided the spur for Ó Súilleabháin to undertake his own autobiographical account of growing up on the Great Blasket. As he wrote, he sent the manuscript to Thomson for comment.

Thomson was an outstanding Greek scholar, and wrote his first book Greek Lyric Metre (1927) while on a scholarship to Trinity College Dublin. In 1931 he was appointed lecturer in Greek at University College Galway, where he taught through Irish. He was able to renew his friendship with Muiris Ó Súilleabháin, now stationed as a Civil Guard only a few miles away in the Connemara Gaeltacht. He encouraged Muiris as he wrote Twenty Years a-Growing, edited the text, co-authored the English translation with Moya Llewelyn Davies, got his friend E.M. Forster to write the introduction, and finally gave some of his own money towards the publication.

While in Galway he wrote four scholarly works in Irish on Greek literature. His early experience on the Great Blasket had given him an insight into the nature of Greek epic poetry and its origins in an oral tradition. Throughout his life Thomson remained one of Britain’s leading Marxist intellectuals. His Marxism and Poetry (1945) remains a classic exposition of its kind.

Towards the end of his life he turned once more to the deep well of memories formed in his youth on the Blasket Island. In 1977 he wrote an essay in Irish An Blascaod a Bhí, followed by an English version, The Island that Was. A revised longer version Island Home appeared just before his death in 1987.

Then I went to Ireland. The conversation of those ragged peasants, as soon as I learnt to follow it, electrified me. It was as though Homer had come alive, its vitality was inexhaustible, yet it was rhythmical, alliterative, formal, artificial, always on the point of bursting into poetry.