Life at Sea

The ability to supplement their diet with fish from the sea saved the Islanders from the worst effects of the Great Famine of 1845-8 in which a million people, dependent almost solely on the potato, had died.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century as the price for fish stabilised and the market for mackerel and lobster expanded, they abandoned sailing boats for the canvas covered canoe or naomhóg. Light and easy to handle, it was well suited to the task of laying and drawing lobster pots. It was relatively cheap and easy to make. They were capable of making one with their own hands from a few simple elements: wood, canvas, tar, nails, some paint.

The Island fishermen experienced a period of modest prosperity towards the end of the nineteenth century. But it was short-lived. Fleets of steam trawlers appeared in increasing numbers among the islands. Small inshore fishermen like the Islanders could not compete. With over-fishing, catches fell and with the fierce competition among the big trawlers prices tumbled. In 1921 there were 400 canoes west of Dingle; in 1934 there were only eighty.

We were seated at our ease without a trouble or a care in the world, thought there is seldom such a thing on a man of the sea. it was a comfortable time – the boat down to the gunwale with fine pollock, not a touch of stress on us as we made for home, but the boat moving east and ploughing the sea before her, as we pulled at our pipes, talking and discussing the affairs of the world.

The gale continued blowing out of all measure through the night, and the little canoe and the man were being swept before the wind through Dingle Bay until milking time next day. Just at that point of the day he was blown into Valentia harbour, himself and his canoe, unhurt and undamaged. He was taken good care of there; he had passed all alone through the storm, and they marvelled that he had not died for very terror in the long, endless night.

I think this is a very confined place, with the sea out there to terrorise me. Ant its out on that sea my husband will spend half his life from now on.

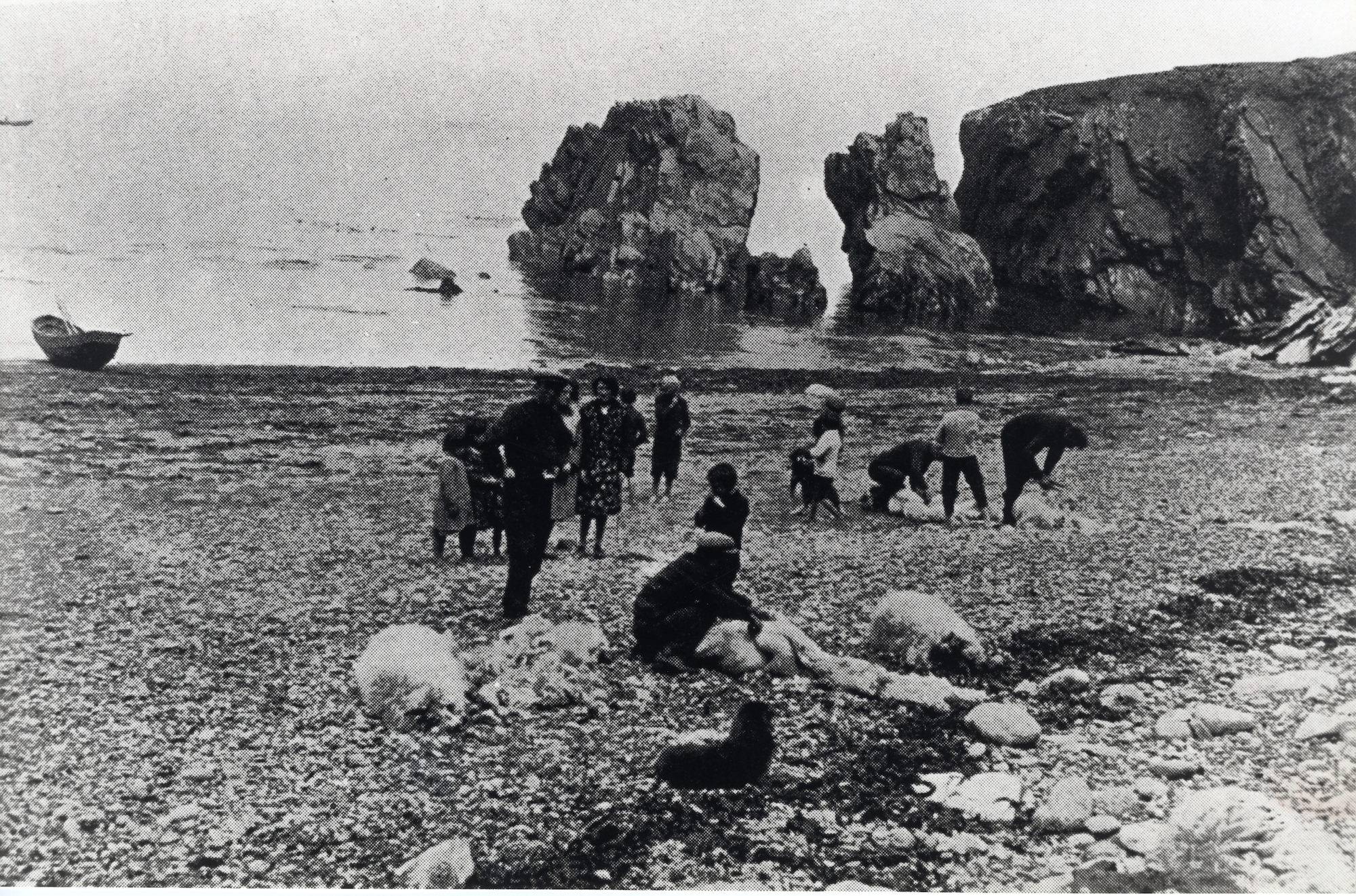

The difficulty of keeping bulls on the Island meant that cows had to be transported to the mainland for insemination. The same effort was needed to get cattle to the market. The naomhóg, capable of carrying a load of half a ton or more, was used for this purpose since about 1880. A bed of furze or heather was prepared in the boat, and the cow then being laid on it with its legs tied.

A second naomhóg always accompanied the boat in which the cow was carried. Unloading the cow at Dún Chaoin was an equally difficult job. The whole operation had to be repeated on the return crossing. The operation was difficult and needed the assistance of up to eight men.

Island fisherman occupied themselves outside the fishing season with repairing equipment and making lobster pots. Osiers had to be cut and fetched from the mainland to make the pots, although long stalks of island heather or blackthorn branches were sometimes used to make the base of the pot.

Hand-line fishing from the rocks is the oldest form of sea-fishing practised in Ireland, and was the only form of fishing practised on the Island until the early nineteenth century. Driftwood was a valuable and welcome bounty on the Island, where timber was always in short supply. Many incidents of large amounts of timber, containers of food, and other kinds of wreckage (and survivors and casualties of shipwrecks) are recorded by island writers.

Factory-produced nets replaced home-made nets around the end of the last century, seen here being repaired with a net needle. The size of the mesh was roughly gauged by the thickness of two fingers. This kind of net is used for catching mackerel. Crayfish and lobster fishing is a relatively new industry in Corca Dhuibhne where it is still practised by fishermen. This rocky coastline of the Island is ideal for lobster fishing.