Island Writers

In the early years of the twentieth century, scholars visited the Great Blasket to learn Irish and to collect folklore.

They encouraged the islanders to write their life stories in their native tongue, and the books they wrote give a unique insight into the hardship of Island life. The three best known Island books are An tOileánach (The Islandman) by Tomás Ó Criomhthain, Peig by Peig Sayers, and Fiche Blian ag Fás (Twenty Years A-Growing) by Muiris Ó Súilleabháin.

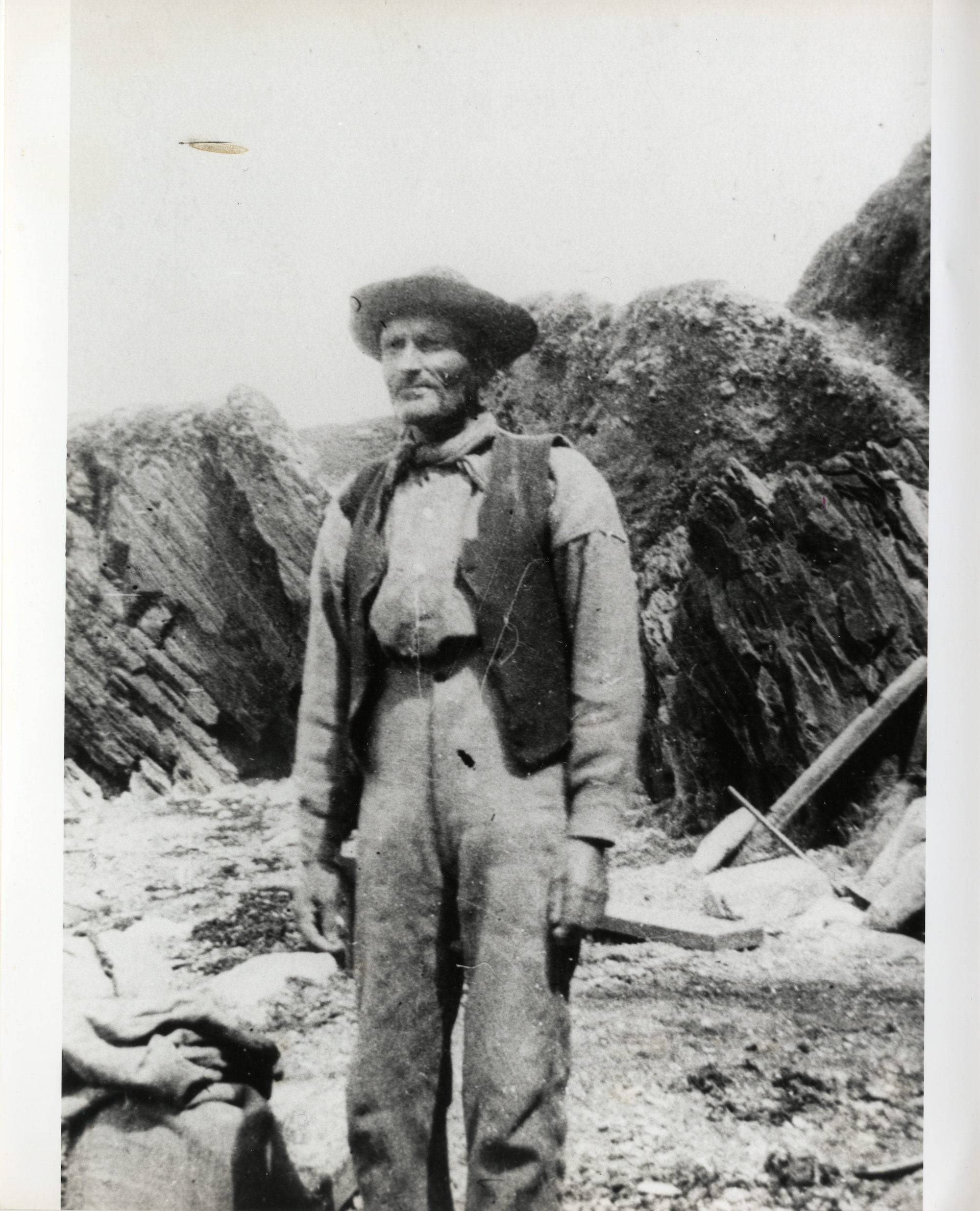

Tomás Ó Criomhthain (1855-1937)

Perhaps the greatest of the Island writers. A farmer and fisherman, he lived all his life on the Island. Having been taught to write only English in school, he was faced in his middle years with the challenge of learning to write in his native Irish in order to record the life and history of his people. He received great encouragement from the scholars Carl Marstrander and Robin Flower and later as editors from Brian Ó Ceallaigh and Pádraig Ó Siochfhradha. His first major book, Seanchas ón Oileán Tiar, published in 1956, was dictated to Robin Flower. But he steadily improved his writing abilities until he was able to produce his two best known works Allagar na hInise (1928), and An tOileánach (1929), in his own hand.

As works of high literary merit coming out of an oral culture, they are triumphs of determination to master the written word – to leave a record, as he wrote in the closing lines of An tOileánach, ‘of what life was like in my time and the neighbours that lived with me’.

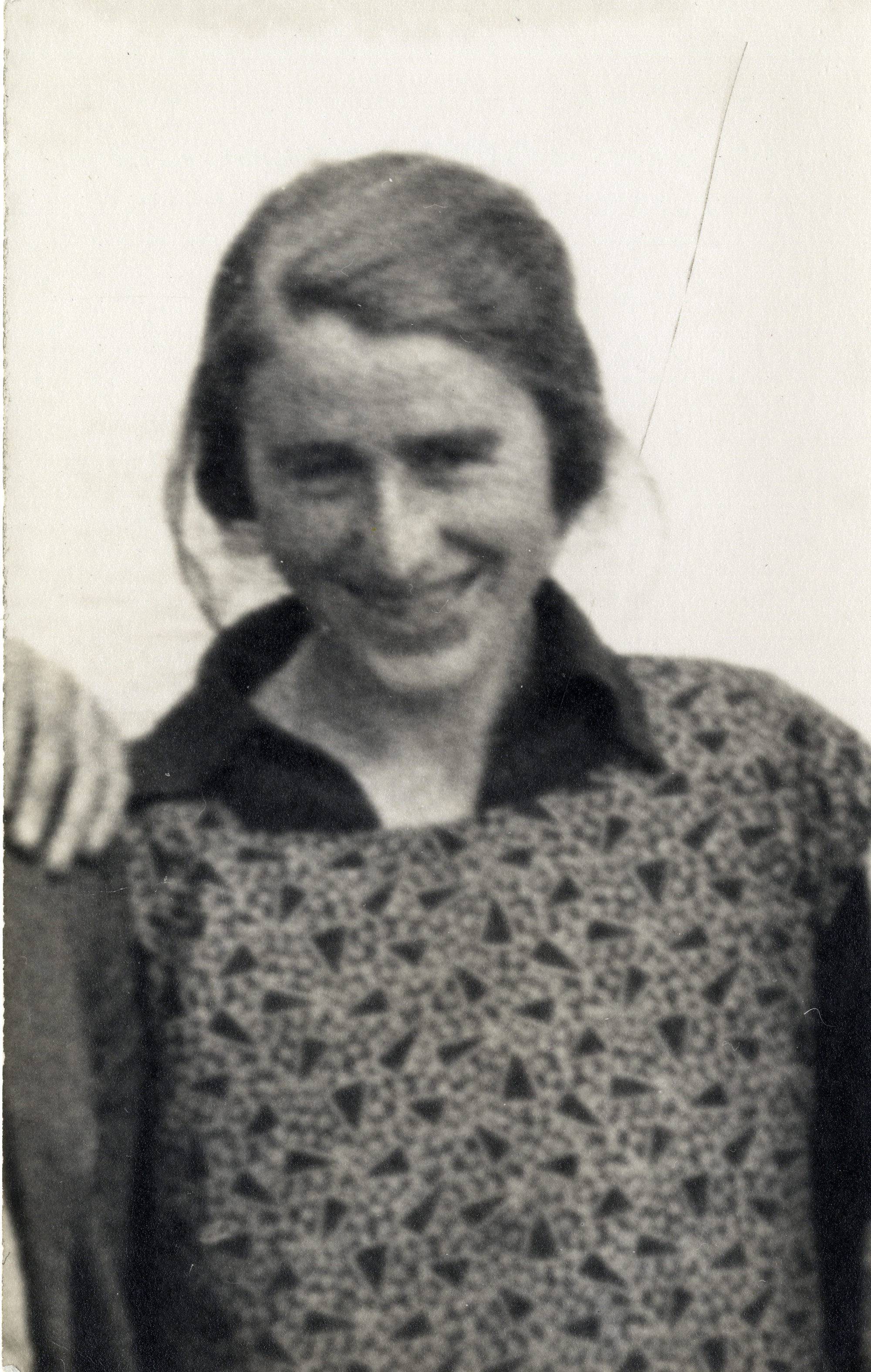

Peig Sayers (1873-1958)

Of the three most renowned Blasket writers, Peig Sayers had perhaps the most traditional world view. Although essentially a personal account of her upbringing on the mainland, her marriage to a Blasket man, and her middle years as a wife on the Island, her autobiographical Peig draws frequently on traditional tales to illustrate her observations. Indeed, before she published her first book, she was recognised for her gifts as a storyteller.

Like others of her generation, she was educated through English rather than in her native language. She never acquired the ability, therefore, to write in Irish, and instead dictated both volumes of autobiography, Peig (1936) and An Old Woman’s Reflections (1939) to her son Mícheál.

Perhaps her most important legacy is the vast collection of traditional tales, songs, and customs dictated by her to Robin Flower, Kenneth Jackson, Seosamh Ó Dálaigh, and others. A fraction of it appears in her Scéalta ón mBlascaod (1938).

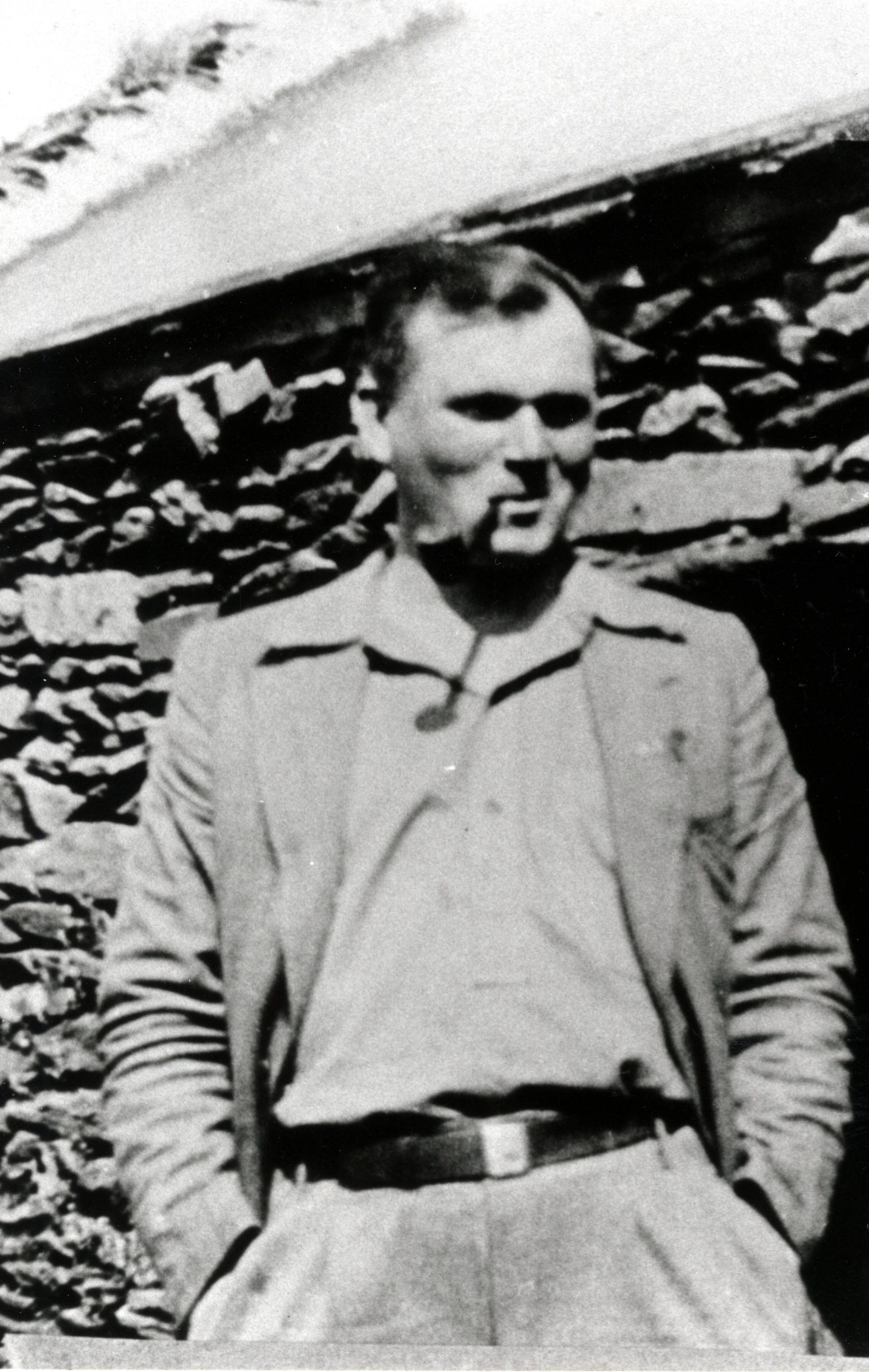

Muiris Ó Súilleabháin

Following the death of his mother, Muiris spent the first six years of his life in Dingle. When he rejoined his family on the Island he spoke only English, but quickly became fluent in Irish. He was greatly aided in this by his grandfather, Eoghan (Daideo) Ó Súilleabháin, a gifted storyteller who developed a great affection for the boy.

It was the success of Tomás Ó Criomhthain’s autobiographical book The Islandman, combined with the encouragement of his friend George Thomson, that prompted Muiris to undertake his own account of his formative years on the Blaskets. The result, Twenty Years a-Growing, was acclaimed nationally on its publication in 1933. The English translation, published the same year by Thomson and Moya Llewellyn Davies, quickly established it as an international classic of autobiographical writing.

The book’s success encouraged Muiris to take up writing full-time, but a second volume of autobiography and a novel were rejected by successive publishers. In 1950 he was drowned while swimming near Galway.

Eibhlís Ní Shúilleabháin (1911-1971)

Chiefly remembered as the author of a remarkable series of letters, a selection of which was published as Letters from the Great Blasket (1978). The selection draws on the lengthy correspondence Eibhlís maintained with an English visitor to the Island, George Chambers, between 1931 and 1951. The letters span her early adult life on the Island and the first decade of her life on the mainland, to which she moved with her family in 1942.

The letters are unique in the context of Blasket literature, not least for being written in English, very much a second language for Eibhlís. Despite, or perhaps because of, being written in halting English, Eibhlís’ letters have an intense, poetic appeal, becoming increasingly elegiac in tone as she records and laments the relentless decline of the Island’s population.

Besides the correspondence with George Chambers, she kept a diary in Irish over the years, making many detailed observations about the social life of the Islanders.

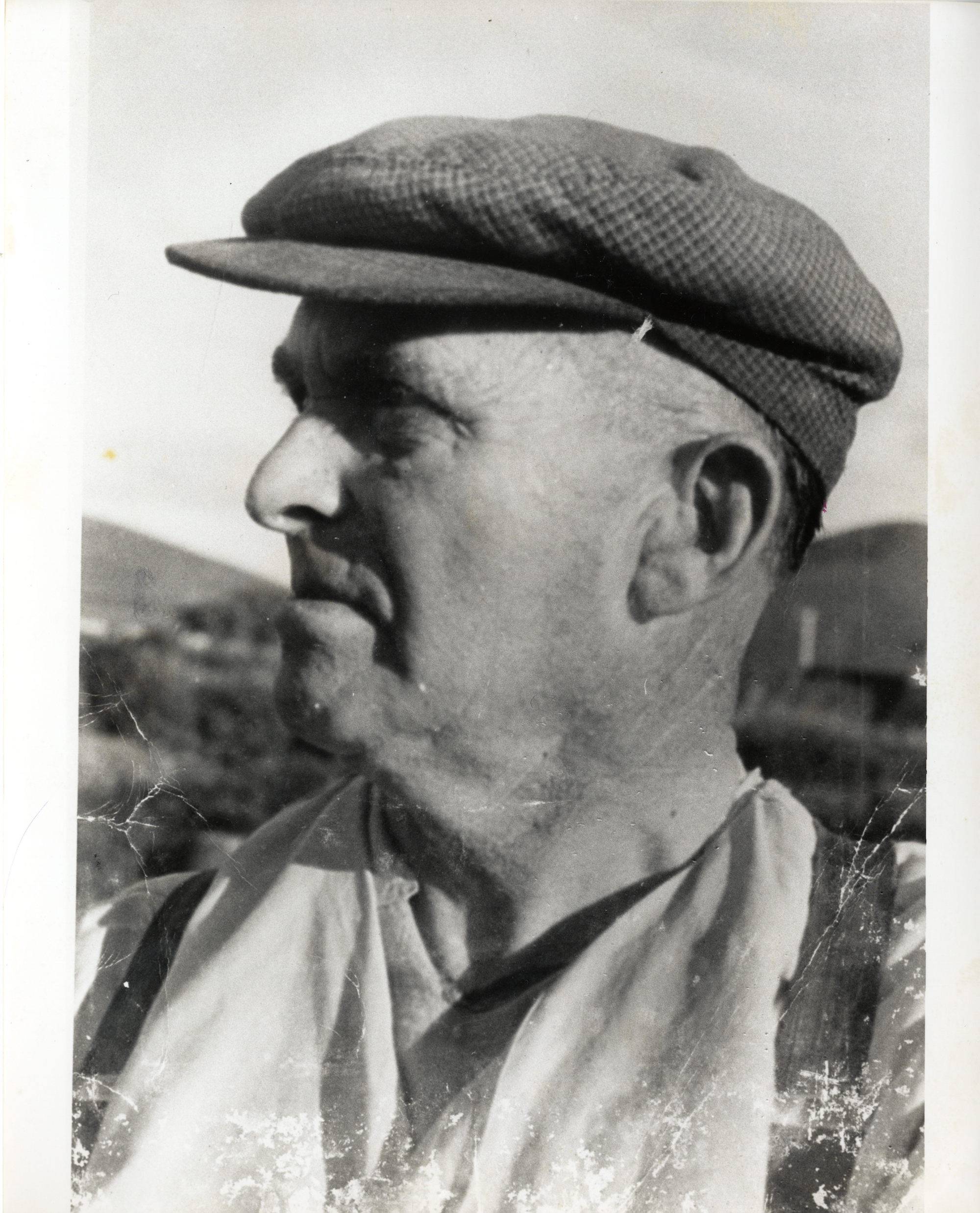

Seán Ó Criomhthain (1898-1975)

The youngest son of Tomás Ó Criomhthain, he married Eibhlís Ní Shúilleabháin in 1933. Together they cared for Tomás in his final years. They moved to Muiríoch on the mainland in 1942, where Seán spent most of his time as a fisherman.

He wrote many essays for Irish journals, and in 1969 his book Lá dár Saol was published. Though clearly influenced by his father’s celebrated autobiography The Islandman, his book is more modern and forward-looking in style. And while the book deals with life on the Island in the 1930s and early 1940s, it goes on to describe the difficulties for a young Island couple of adapting to life on the mainland after they had left the Great Blasket in 1942. After his death in a road accident in 1975 a second book, Leoithne Aniar, was published posthumously in 1982. It contains a detailed account of the Island’s history, composed in a more formal and detached style than his father’s.

Máire Ní Ghuithín (1909-1988)

A grand daughter of the Island King Pádraig Ó Catháin, Máire moved to the mainland after her marriage to Labhras Ó Cíobháin from Dún Chaoin. The urge to write came relatively late in her life and over a quarter of a century after the final evacuation of the Great Blasket. She was encouraged by an Englishwoman, Joan Stagles, who taught herself to read and speak in Irish and who, together with her husband Ray, wrote extensively about the history of the Blaskets. Both of Máire’s books An tOileán a Bhí (1978) and Bean an Oileáin (1986) contribute to an understanding of the social life and material culture of the Blaskets and west Kerry. Particularly important are her detailed descriptions of the customs associated with birth, marriage, and death in the early years of the twentieth century, and her accounts of the seasonal and daily routines of Island life.